A poetic exploration of the Tel Aviv University's shelter signs and the Talmudic Cities of Refuge

[Published in The Tel Aviv Review of Books, Winter 2021; Translated by Alex Stein]

In 1947, the first edition of Even-Shushan, the modern Hebrew dictionary, was published. It was the first Hebrew dictionary to include the word “shelter” without the connotation of the shelter from the biblical-Talmudic “city of refuge.” Thus, instead of being a demilitarized area in which no weapon is allowed, “shelter” becomes “a fortified structure protected from blasts and bomb ricochets, at times from a direct hit as well,” which, according to the dictionary, you can occasionally fire weapons from.

In the paths of Tel Aviv University, leading between the Sourasky Library and the Wolfson Building of Engineering, I return with my thoughts to the older “Ben Yehuda” dictionary, as if to an outdated sign: “give yourselves the cities of refuge… a murderer escapes there… they will be a shelter from the blood avenger…” Relieve us from the cycles of vengeance, I mumble to myself, the glorious shade-giving vaults to my right, pebbles under my feet, birds chirping around me—you shall create cities like Sheikh Munis, relieving its pains alongside ANU Museum of the Jewish People, and the Arabic words are not erased from the dictionary—like “Ben Yehuda,” I am still interested in the relation between languages. True, “Ben Yehuda” is old and foreign. But still, it is in the library, not far from here, there is even more than one copy. Maybe there ought to be signs leading to “Ben Yehuda?” Yes, maybe that shall be my calling, hanging these signs around campus. Cheap, mobile signs, urgent, desperate, arrow-filled, here, there: a protected space. A city of refuge. Shelter shelter. And if I manage to be persistent and not let the days wear out my body, maybe in the future there will be more and more of them. More and more resources for the rampant, all-too-human violence, dripping pollutant blood, violence that the Talmudic sages knew, because their state was already destroyed, is impossible to keep hidden, in architectural design and alienated concrete. “Shelter shelter,” I mumble. Turning, turning in space. Capturing the signs within it.

In the paths of Tel Aviv University, leading between the Sourasky Library and the Wolfson Building of Engineering, I return with my thoughts to the older “Ben Yehuda” dictionary, as if to an outdated sign: “give yourselves the cities of refuge… a murderer escapes there… they will be a shelter from the blood avenger…” Relieve us from the cycles of vengeance, I mumble to myself, the glorious shade-giving vaults to my right, pebbles under my feet, birds chirping around me—you shall create cities like Sheikh Munis, relieving its pains alongside ANU Museum of the Jewish People, and the Arabic words are not erased from the dictionary—like “Ben Yehuda,” I am still interested in the relation between languages. True, “Ben Yehuda” is old and foreign. But still, it is in the library, not far from here, there is even more than one copy. Maybe there ought to be signs leading to “Ben Yehuda?” Yes, maybe that shall be my calling, hanging these signs around campus. Cheap, mobile signs, urgent, desperate, arrow-filled, here, there: a protected space. A city of refuge. Shelter shelter. And if I manage to be persistent and not let the days wear out my body, maybe in the future there will be more and more of them. More and more resources for the rampant, all-too-human violence, dripping pollutant blood, violence that the Talmudic sages knew, because their state was already destroyed, is impossible to keep hidden, in architectural design and alienated concrete. “Shelter shelter,” I mumble. Turning, turning in space. Capturing the signs within it.

*

I begin with the sign closest to where I am now sitting, at the entrance to the Sourasky Central Library. This, without a doubt, is the best-looking sign on campus, elegantly aligning with the library’s 1970s style. It is modest and meticulously designed. The font, the camel-beige and bottle-green shades, the modernist lines of the arrow pointing downwards, its position within the aesthetic, angular lines of the staircase, all these coordinate gracefully with the rest of the geometric shapes scattered in the space: the circles of ceiling lights from above and the glass squares beneath, as well as the reddish-brown benches resembling the corduroy commonly seen in police television shows of that era. Some elements of the sign disturb the sense of elegance. It hangs somewhat crookedly, the screws holding it in place are rusty, and its borders are made of plastic paint that must have escaped the painter’s brush during a redecoration. Well, this is Israel, after all, at an entrance to a building that is not the MoMa, after all this is a service sign which was probably added after construction was finished.

I begin with the sign closest to where I am now sitting, at the entrance to the Sourasky Central Library. This, without a doubt, is the best-looking sign on campus, elegantly aligning with the library’s 1970s style. It is modest and meticulously designed. The font, the camel-beige and bottle-green shades, the modernist lines of the arrow pointing downwards, its position within the aesthetic, angular lines of the staircase, all these coordinate gracefully with the rest of the geometric shapes scattered in the space: the circles of ceiling lights from above and the glass squares beneath, as well as the reddish-brown benches resembling the corduroy commonly seen in police television shows of that era. Some elements of the sign disturb the sense of elegance. It hangs somewhat crookedly, the screws holding it in place are rusty, and its borders are made of plastic paint that must have escaped the painter’s brush during a redecoration. Well, this is Israel, after all, at an entrance to a building that is not the MoMa, after all this is a service sign which was probably added after construction was finished.

This is one of the things I find odd about the shelter signs throughout the campus. Why is it that they are hung as if they were an afterthought, as if the architect did not know that there would be a shelter, a space that should be easy to find if necessary, with proper signage? Why do most of these signs seem like an element added unexpectedly: a guest someone forgot to invite, the one you set a chair for at the last minute with the hurriedness of guilt-ridden hosts?

On the way to the elevator, a meter or two from the previous sign, I find two others. One is printed on a sheet of A4 paper, laminated in a hard translucent cover, screaming urgently in red, “The shelter is on the basement floor, please use stairs only,” with arrows pointing downwards. The other is subtle, a modest-sized silver rectangle, framing the monochromatic shift between letter and background.

On the way to the elevator, a meter or two from the previous sign, I find two others. One is printed on a sheet of A4 paper, laminated in a hard translucent cover, screaming urgently in red, “The shelter is on the basement floor, please use stairs only,” with arrows pointing downwards. The other is subtle, a modest-sized silver rectangle, framing the monochromatic shift between letter and background.

The silver sign is an organic part of a pre-planned group of service signs, designed with the cool splendor of modern nobility that the library’s design imitates. This sign only hints at the direction of the shelter. Moreover, thanks to a unifying/dividing slash it even minimizes its utility, which is apparently an appendage to another necessary yet awkward space—the lavatory. According to this sign, the shelter is part of a split hierarchy (lavatory/shelter), marking it out from the other locations listed in this grouping: a printing center; a photocopying room; a study hall; and rooms for Jewish education, theatre, Israeli music, and university archives.

In the Faculty of Humanities, located in the Gilman Building, the stairs are the designated “protected space” for emergency situations, despite not leading to an exit. There are two printed signs hanging from the ceiling, each with an arrow to direct people. These have also been laminated with the same cheap materials. One is in black, with directions in English to the “Designated Shelter Area,” which is hard to precisely locate. The second is in burgundy, presenting far clearer instructions in Hebrew: “To the Protected Space (merhav mugan), Stairwell.” The word “shelter” (miklat) is absent from the Hebrew sign.

In the Faculty of Humanities, located in the Gilman Building, the stairs are the designated “protected space” for emergency situations, despite not leading to an exit. There are two printed signs hanging from the ceiling, each with an arrow to direct people. These have also been laminated with the same cheap materials. One is in black, with directions in English to the “Designated Shelter Area,” which is hard to precisely locate. The second is in burgundy, presenting far clearer instructions in Hebrew: “To the Protected Space (merhav mugan), Stairwell.” The word “shelter” (miklat) is absent from the Hebrew sign.

We are now led towards a different space, adopted as the default choice for a building erected before the missile attacks of the 1991 Gulf War. Missile attacks are now a more common occurrence with the regular exchange of fire between Israel and Hamas in the new millennium. As always, the arrows point upward when they should be pointing straight ahead, creating an unconscious bureaucratic connection between land and sky.

The Gilman Building has architectural pride. Like the library, it opens inward to patios, bringing daylight to its corridors. The intention is to introduce greenery into the building. The mission is barely accomplished, but at least it demonstrates some of the building’s ambitions for the hundreds of students passing through its rooms and corridors. Who would have thought that its stairs would have to provide shelter, here, where peace was already supposed to reside?

Yes, sometimes this pause happens, the awkwardness of rushing quickly to a stairwell, staying there, like inanimate objects, skipping a beat with every rattling sound or laughing at the mere idea of being scared, reciting names of loved ones, Arab and Jewish, outside or closer to Gaza, feeling an immense pain from the IDF’s massive retaliation, preparing for a son’s recruitment (despite our hopes, despite every escape route we calculated, he will in fact enlist in a year), defeated, somehow accepting this ongoing life with no horizon and with no solution. Becoming angry at those who abandoned the land. Trying to have an impact in some way: reading events, testimonials, friendships.

These unplanned signs also provide a moral compass, printed by anonymous figures (a janitor? a secretary?) who do not usually make any great announcements. The signs capture some of the awkwardness, the panic, as well as the forgetfulness, as if to say, “we are not wanted here, but there is no choice.”

Beneath the Gilman signs, the camera catches another weird merger between a well-designed building and wild randomness: metal lockers that had been taken out of one of the rooms. Are they, like the signs, waiting for a decision, an affiliation? Or, like sculptures, are they just standing there? Wondering about transitional periods that have become part of a routine.

Made of tin, more solid than the laminated paper and resistant to the weather; how intrusive, vulnerable, ruined, and unkept this sign is. A sort of reminder of the poor shtetl or Al-Mlah, the Jewish quarter of Morocco’s cities, where any cultivation is temporary and with little means, reminder of a military mindset in which beauty is an excessive indulgence; like a tear left by hasty construction, tower and stockade, transit camps, low-level housing, wrecking villages, in this temporary vulnerability, indicating an erased past (Arab, Eastern European, and Eastern), this sign hangs at the entrance to ANU, the Museum of the Jewish People, as if to mediate to us the essence of our dash to the shelter.

Here, the sign is in Hebrew and English; but just like in the Gilman Building, the words are different. The upper part reads “protected space” in Hebrew, the bottom part reads “shelter” in English. I wonder about the meaning of these relaxing, amorphic words, “protected space”: do they exist to disguise the fact that there is no actual protected space here?

Is this an improvised space, or has it been upgraded over the years? And why the difference between the Hebrew and the English? Anu Museum (Beit Hatfutsot) opened in 1978; like the library, the building looks like a brutalist bunker, closed to the outside. There were no standards for protected spaces when it was built, but it is made of concrete regardless. It’s a confusing by-product of the zeitgeist, a side effect of the trauma that the nation who built it had been through, with concealment a part of its identity; only now it has erased all the mystery from it, given it freedom and pride and turned the entire campus into its covert spokesperson.

The tin sign’s wounds almost crumple the determined arrow, the granulite wall showing through them. Above it lies a dried-up bush, looking like a deserted nest. It seems to me that the wounds are requesting an opposite motion—not to run forward quickly, but to actually stop and think: “What protects?”, like a glum, uncanny poem appearing on campus instead of in a book.

After a long while in the library, I take a rejuvenating walk and presently find myself at the Wolfson Engineering Building. The charming surroundings create a pleasant walking path, a true oasis in the sweltering Tel Aviv heat. Even at noon, shade can be found in the spectacular corridor of vaults running around the building, which was designed by the American-Jewish architect Louis Kahn. The shade creates a feeling of being inside and outside at the same time, next to the wonderous palm trees, a path made of pebbles winding between straight lines, and the birds chirping. Those who enter the building encounter a sign bearing the motto: “Those who fall in love with the problem are the ones who find its solution.” I wonder whether I have sufficiently fallen in love and whether there is truth in these words.

As in the library, there are three signs here giving directions to a shelter. We have seen two forms of these improvised signs already. A tin sign with a clear arrow that reads “protected space” in Hebrew and “shelter” in English (this time in blue instead of red), and near it another sign, a simple sheet of unlaminated paper, A4-sized and printed in black, plastered on the glass wall of the entrance hall. The third sign sits between the other two, close to the tin sign. It is the manicured service sign. A serene blue background indicates with a clear arrow the direction to the synagogue. At its center is a white rectangle, wrapped in clear PVC and framed by a thin silver stripe, with the accompanying detail: prayer times, with weekly, monthly, and festival Torah readings. In the upper left corner, a sort of wrinkle serving as a reminder, the shelter is marked within an elliptical cloud coloured in a fog-like burgundy. The heavenly blue is interrupted by the color of earth and blood, the color of a human, but in a vapid low dosage. Here too, as in the Sourasky Building, the shelter is depicted as an appendage to another space. In this case, when necessary, we will not gather in the lavatory but in the synagogue. And again, the location of the shelter is only hinted at.

Like the doll behind the scenes operating the fingers of history in Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History, the casual nature of shelter as reflected by the signs conceals what is evident to all: we are living in one big shelter. All these concrete buildings that forgot the Arab village of Sheikh Munis (upon whose ruins the city of Tel Aviv stands) and refused (or were too poor) to display Europe’s classical beauty, they—promising rationality and improvement—are all a shelter. Bunkers, in Paul Virilio’s words. In his book Bunker Archaeology, he discusses the impact of the Atlantic Wall while contemplating its remains: “These heavy gray masses with sad angles and no openings – excepting the air inlets and several staggered entrances – brought to light much better than many Manifestos the urban and architectural redundancies of those postwar period that had just reconstructed to a tee the destroyed cities.”

The designed signs of Tel Aviv University reveal the architectural hope of an idyllic world. It’s actually the hope of the entire campus, a testimony of the status it wishes for and, to a significant degree, provides. But the awkwardness of the signs from the perspective of the shelter itself, its existence somewhat overtaking their without noticing, raises questions, terrifying and even funny. It’s like looking at a king who has failed to noticed the stain spreading across his posterior. By contrast, the improvised signs indicate the urgency created by the shattering of thoroughly constructed hopes. They bring to mind some crazed, fearless grandmother, going alone into battle, her hair swept into a loose, sweaty updo. She, who has had enough of young parents’ attempts to raise their children perfectly; she, who cannot stand their exhaustion when they fail to meet the goals they set for themselves, turns to the suffering of the grandchildren who cry for her, demanding to know reality outside of official broadcasting screens and prints and laminates, and adds arrows in sharp colors: up, sideways, down, there. Here. “Shelter.” “Shelter.” But mightn’t this shelter, regardless of its concrete fortitude, get blown away like the paper the sign was printed on?

*

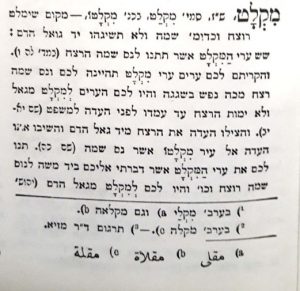

“Shelter shelter was written in the intersection for the murderers to know to go there”

(Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, 8:5)

Regarding the city of refuge in the Talmud, which is what I am reading about in the library, there are signs. There is also an overflow of material indicating urgency, difficulty and embarrassment: the word shelter is written again and again as a printing error. But the Babylonian Talmud stares directly at the embarrassment, and that is what it deals with, because the ancient city of refuge is not meant for the innocent but for those who murdered unintentionally, those embarrassing, semi-shady beings, the guilty-innocent. At first, it seems that such beings are rare, but there are many access routes stretching between the cities of refuge, and the abundance of signs giving directions to them suggests something different. So too the number of cities, ranging from six to 48, and in better days to come there will be more and more and more of them. The sages of the Talmud see the text on the cities of refuge, the text studied itself, as a city of refuge. Its purpose is to take in any person wanting to take responsibility for unintended acts of violence as well as any that they might commit in the future. Therefore, this applies to many people, maybe even all of us. There, in the paths of ancient imagination leading to the cities of refuge, walked the accidental murderer, who must be banished. He must have run through them and not walked. Ran and escaped the blood-avenger. Thus, the paths must be cleared regularly, so that there will be no obstacle in the banished person’s way, to make sure that they are at least 32 cubits wide and there will be signs on every intersection: “Shelter Shelter.”

According to these rules, the entire country is woven with paths and signs directing to shelter provided by cities of refuge, a territory everyone can turn to, at any given moment. As if taking a life unintentionally, and becoming a murderer, is something that happens often, an ordinary event, ordinary life accepting such irregular occurrences. Banishment. Flight. Tolerance for more than rage and simple justice. For that, the paths must be wide enough, and the signs must bear the double wording, “shelter shelter,” like a shout or a double reading of the tongue, accumulating the tonal mass of the word, losing the light hold of the meaning. “Shelter shelter”: the visuality of the text sinks into the mind. It must have been special, because which other signs present the same word twice?

In the wide paths leading from the Sourasky Library to the Wolfson Engineering Building, I walk and look at the signs. I look at those hiding the shelter whilst announcing its presence and at those shouting its presence urgently. I walk knowingly: they do not lead to the ancient Hebrew-Babylonian shelter.

I am asking again: maybe there ought to be other signs around campus, leading to the old dictionary on the library shelves? Cheap, mobile signs, urgent, here, there: A city of refuge. Shelter Shelter.

*This essay is Tile #171 from the project “City of Refuge, 963 Tiles.” The project includes an essay book about Tel-Aviv, a PhD in Literature and text installations. The number of the tiles (963) is the number of tiles covering the doors of the shelter dug underneath Ha-Bima Square in Tel-Aviv, where I wrote a diary for a year, from Autumn 2014 until Autumn 2015, following the war in Gaza.